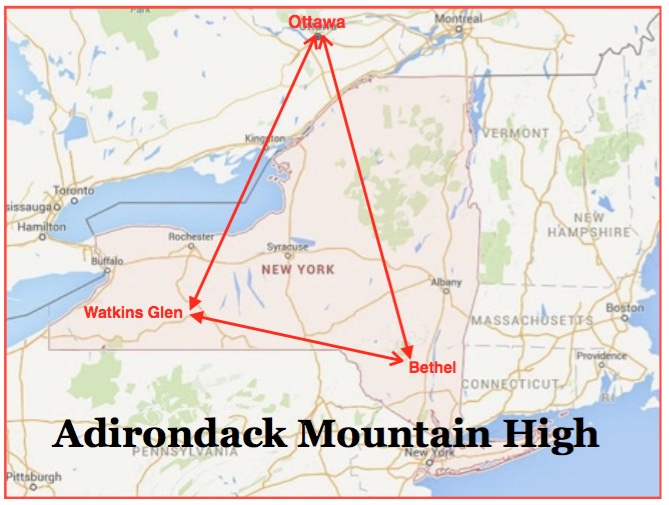

For a few remarkable days in August of 1969, a 600 acre meadow in upstate New York, seemed to have become the center of the universe. Multitudes had been drawn to the little town of Bethel, for an event called the Woodstock Music and Arts Festival and I, a very young police officer, found myself smack-dab in the middle of things.

As an aside, this event would have been cancelled at the last minute had a local dairy farmer named Max Yasgur not stepped into the breach. By opening his property to the festival, Yasgur allowed some 400,000 youngsters to seek (as the saying goes) “Peace, Love and Music” while, at the same time, making himself an instant hero in the hippie community. Yasgur’s farm, by the way, is now registered as a State and National Historic site, where it continues to draw visitors to a variety of music and cultural events, and a first-class museum.

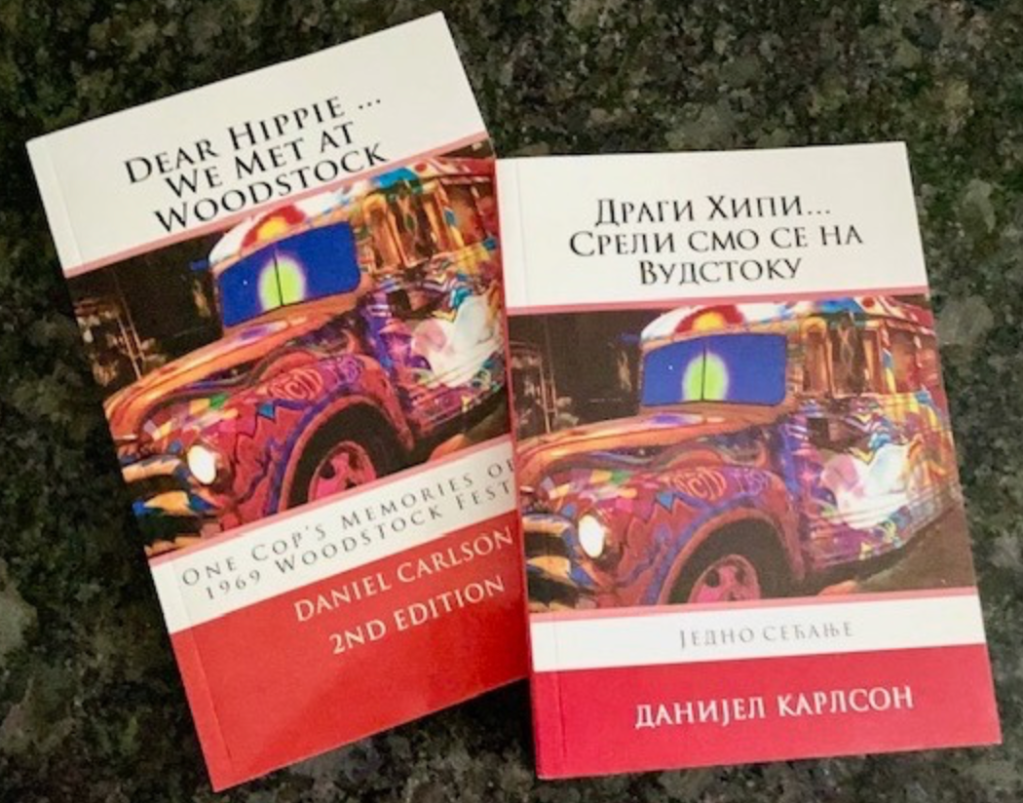

When the festivities finally ground to a halt and I headed toward home, I found myself reflecting less upon the rain, mud, traffic and overwhelming crowds, and more about the many cooperative, helpful and resilient youngsters with whom I had interacted.over those magical days. Touched, deeply, by what I had experienced, I recorded my thoughts in a brief book titled: Dear Hippie, We Met at Woodstock … One Cop’s Memories of the 1969 Woodstock Festival.

By the way, given the fact that Woodstock was marketed widely in the Northeastern United States, one could easily be forgiven for thinking that attendees came only from across America. In actuality, young folks from a number of countries attended and, as some may recall, the event received extensive reportage in the international press and broadcast media.

The worldwide interest in Woodstock continues to this day in several countries including Poland, where an annual free rock festival called the Poland Rock Festival (formerly known as Woodstock Festival Poland) has taken place annually since 1995. Inspired by the original Woodstock Festival, this event draws some 750,000 attendees each year, making it one of the biggest music festivals in the world. (Note the concert logo above)

In Serbia, the international connection to Woodstock is reflected not only in the rock concert at Hajduk Fountain in Belgrade, but in interest in my book, Dear Hippie, itself. When a Serbian editor contacted me requesting permission to translate and then distribute the book, I was surprised and gratified that continued interest in Woodstock might warrant publication in the Balkans. When the book was ready for distribution, esteemed Bosnian and Serbian writer and journalist, Muharem Bazgulj, had this to say in his introduction:

We are living in a time in which people lack the feeling of the authenticity of experience. In the choice between freedom and safety, safety is chosen as a rule. Smoking is reduced to “vaping”, drinking squeezed juices and non-alcoholic beer, even decaffeinated coffee. People may be healthier, but not happier.

The twentieth century, especially in its second half, was not like that. This time saw a tremendous rise of popular culture, especially in the 1960s and 1970s. Then, as a rule, people had, as one modern philosopher would say, “skin in the game”. The most recognizable symbol of that time was Woodstock. There is no person, at least in my generation, who has no association with Woodstock. That association is mainly universally similar: it would have been wonderful to be there in mid-August 1969.

Later on, especially in the Internet era, information about Woodstock has become available to everyone, but again there is hardly a more unusual view of Woodstock than the one offered us by Daniel Carlson’s wonderful book “Dear Hippie…We Met at Woodstock” with the subtitle “One Cop’s Memories of the 1969 Woodstock Festival”. Stories about Woodstock are mostly told from the perspective of visitors or possibly a performer, but Carlson found himself there as a police officer.

Bazgulj concluded by lavishing praise upon Biljana Kocanovic’s remarkably accurate translation, and I would agree with his assessment. It was Kocanovic’s vision and energy that brought this project to fruition, and I am eternally grateful for her hard work.

Dear Hippie is now available in bookstores in Serbia and, while I do not expect to be summoned to book signings in Belgrade any time soon, it is gratifying to know that interest in Woodstock continues to resonate, and that my book may have some small role in helping that spirit persevere.